Cobalt Strike Beacon Analysis

I've written before about how servers with open directories can make it easy to deploy malware but in this post I'll explore a benefit of a single open directory on a site, https://beaconbeagle.com/, which hosts configuration files of Cobalt Strike beacons.

Thanks to some link sharing by the CuratedIntel group, this site caught my curiosity by providing IPs hosting Cobalt Strike beacons and the decoded configurations of the payload associated.

Beacon Configs

Cobalt Strike leverages an implant (beacon) that relies on a malleable C2 profile which stores the beacon configuration. The official docs for building Cobalt Strike configs can be found here.

Parsing these configurations can uncover atomic indicators that are useful for filtering on known profiles. Something Censys had recently posted about.

Some useful fields in a config file include:

- watermark - a unique value associated with the Cobalt Strike license

- SETTING_PUBKEY - the RSA public key of the beacon

- SETTING_DOMAINS - the beacon IP and URI path used to interact with the beacon

- SETTING_SPAWNTO_X64/X86 - what process to startup as a child process

- SETTING_USERAGENT - what user agent the beacon uses

I had tried years before when learning Golang (emphasis on learning) to uncover Cobalt Strike beacon IPs by their JARM signature and attempt to extract the configuration in order to conduct further malware analysis. The code was messy but the feature was there.

Looking back, one issue I had when writing this was the forced reliance on VirusTotal and the Nmap script to parse said beacon config. With a site like BeaconBeagle hosting a large number of configs readily available, that eases the prerequisite of obtaining configs so that more time can be spent on uncovering patterns between profiles.

Analysis

Given this random set of IPs, I built a Jupyter notebook to merge everything into one dataframe with the goal of finding similarities and differences amongst Cobalt Strike configurations in near real-time. This notebook should be treated as a "in-progress notebook" and not a guide on finding something specific across beacons. I'm creating this as a way to practice Python and Jupyter and sharing because some observations were quite interesting.

Since this site hosts well over 500 files and I'm not sure how often configs get added / updated, this notebook first checks if the filename exists or if the file itself has a newer "Last-Modified" value meaning the data within the file might've been updated. With all of the files downloaded, they're then appended into a dataframe where analysis can begin.

As of writing right now, there are 562 beacon configurations. This includes both x64 and x86 architecture.

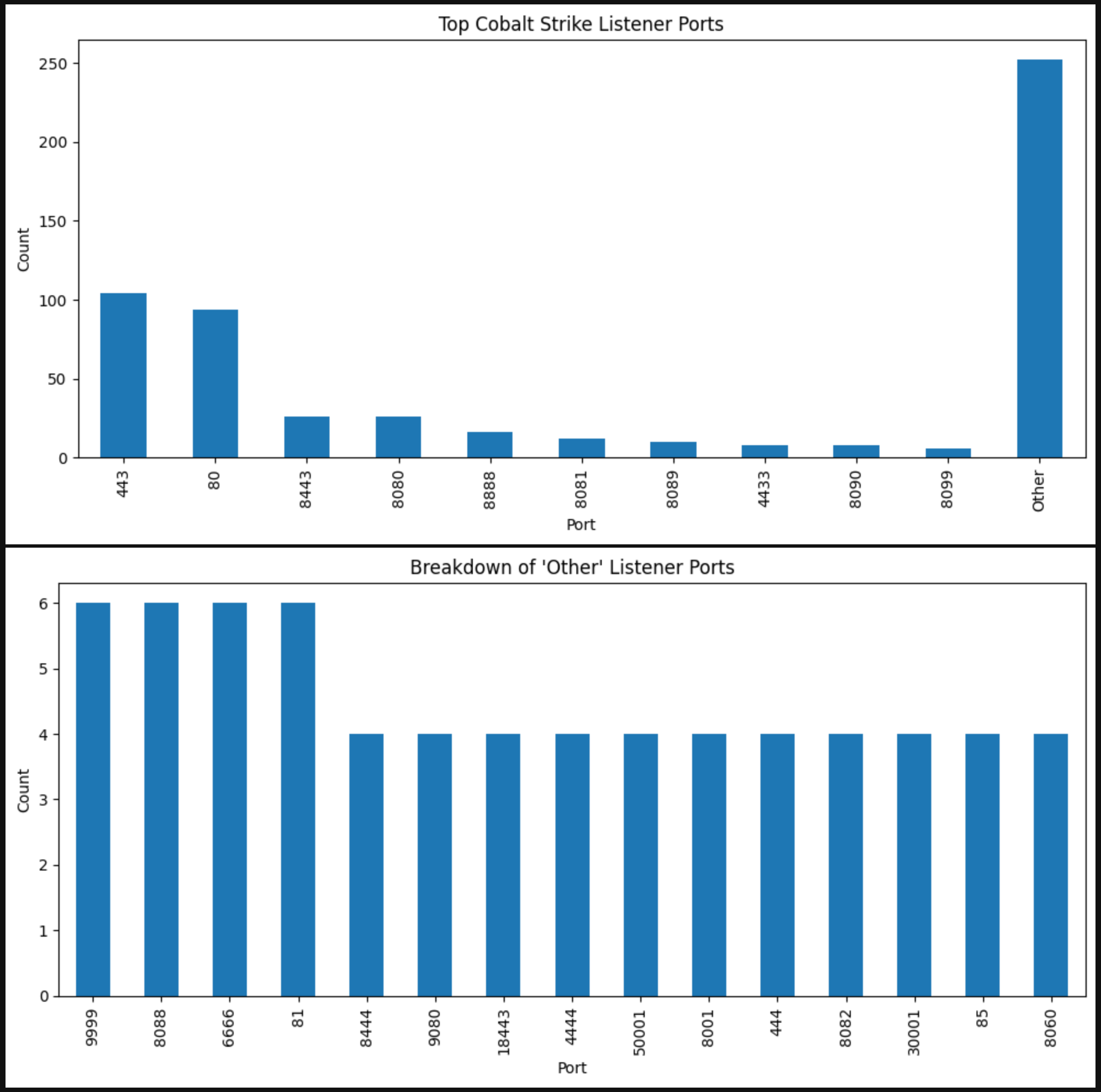

Group By Listener Port

The first idea I had was to group everything by port to uncover the most common beacon listener ports.

With 116 different ports, I didn't want to count all of them since these are malleable profiles so realistically any port could be chosen. I chose the top 25 but split them into two graphs since the "Other" column was an extreme outlier. The first graph shows the top 10 ports. The second graph is the same but for visual reasons as to why I split the "Other" column, you can see that is where a large variance lies. The third graph takes that variance and shows the top 15 ports. Since these ports are modifiable, the rest of the IPs use a unique port or at most share it with 3 other hosts (including the same IP across both architectures).

I should add that the results here don't group by unique IPs. The reason being beacon configs don't have a field for the "IP" but instead the "SETTING_DOMAINS." For example, there are 6 listeners on port 9999 but when inspecting the data, there are overlapping IPs with different URIs.

| source_file | settings.SETTING_DOMAINS | |

|---|---|---|

| 78 | 150.187.25.242-9999_x64config.json | 150[.]187[.]25[.]242,/pixel,116[.]203[.]31[.]207,/j.ad |

| 226 | 117.72.242.9-9999_x64config.json | 117[.]72[.]242[.]9,/load |

| 244 | 49.235.177.231-9999_x86config.json | 49[.]235[.]177[.]231,/dpixel |

| 309 | 150.187.25.242-9999_x86config.json | 150[.]187[.]25[.]242,/en_US/all.js,116[.]203[.]31[.]207,/activity |

| 426 | 117.72.242.9-9999_x86config.json | 117[.]72[.]242[.]9,/ca |

| 432 | 49.235.177.231-9999_x64config.json | 49[.]235[.]177[.]231,/activity |

Without much work already, an additional Cobalt Strike beacon has been found. In rows 78 and 309 is an IP, 116.203.31[.]207, which doesn't currently exist in the dataset but does exist in the ThreatFox database.

After this analysis, I created four additional columns in the dataframe. The first line extracts the IP, Port, and Architecture from the filename. The second line extracts the URI path from the SETTING_DOMAINS column. This makes it very easy to group results going forward.

final_df[["ip", "port", "arch"]] = final_df["source_file"].str.extract(r"(?P<ip>[\d\.]+)-(?P<port>\d+)_(?P<arch>x\d{2})config\.json")

final_df["uri_path"] = final_df["settings.SETTING_DOMAINS"].str.split(",", n=1).str[1]| ip | port | arch | uri_path | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 193.37.69.43 | 95 | x86 | /updates.rss |

| 1 | 139.196.41.201 | 30001 | x64 | /fwlink |

| 2 | 136.115.102.225 | 44444 | x64 | /cm |

| 3 | 179.43.186.214 | 80 | x86 | /push |

| 4 | 154.12.36.140 | 80 | x64 | /__utm.gif |

Group By Public Key

If multiple beacons share the same public key, it's likely they're related and can be grouped together.

These 9 IPs all share the same public key and while they don't all exist under the same ASN, distribute the same file, etc. they can still be linked by a common infrastructure key.

Going a step further, these public keys can be grouped together to aggregate results with any other columns. In this table, I group public keys and view the number of IPs associated, how many ports are being used, number of URI paths, how many config files contain that key and the number of different Cobalt Strike versions that are used.

| unique_ips | unique_ports | unique_paths | configs | version | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| settings.SETTING_PUBKEY | |||||

| 640f18232741807f5bc93c7deaba8d09d302929a0e9fe5c0f877a956256df3d9 | 10 | 8 | 13 | 20 | 1 |

| b2f0552a10f9f88e1c4efdbf9da92ed084a8d7d25b5b33820720577d75c0db23 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 1 |

| 35ad01692eecf13a1a36b5fc11bd242b8d49012517c02a82e8dc38103c02e6a3 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 1 |

| 21ff573a0cf0fcc29c9228ed22d5e364c3fe6497567ac6584a3c9455831b758e | 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 2 |

| 2c6357bcc7958af1622094b71f13c071a8ff003696829f7ada5a072d799badba | 3 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2 |

That second to last PUBKEY is interesting because there's only one IP but two Cobalt Strike versions. I filtered down on that value and it appears the x64 beacon returns "Unknown" but the x86 version returns "Cobalt Strike 4.9 (Sep 19, 2023)"

| arch | ip | port | uri_path | version | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 39 | x86 | 83.229.125.47 | 8090 | /cdn/jquery-3.6.0.js | Cobalt Strike 4.9 (Sep 19, 2023) |

| 146 | x64 | 83.229.125.47 | 8022 | /static/jquery.min.js | Unknown |

| 263 | x86 | 83.229.125.47 | 8080 | /static/jquery.min.js | Cobalt Strike 4.9 (Sep 19, 2023) |

| 414 | x64 | 83.229.125.47 | 8090 | /static/jquery.min.js | Unknown |

| 503 | x64 | 83.229.125.47 | 8080 | /cdn/jquery-3.6.0.js | Unknown |

| 526 | x86 | 83.229.125.47 | 8022 | /static/jquery.min.js | Cobalt Strike 4.9 (Sep 19, 2023) |

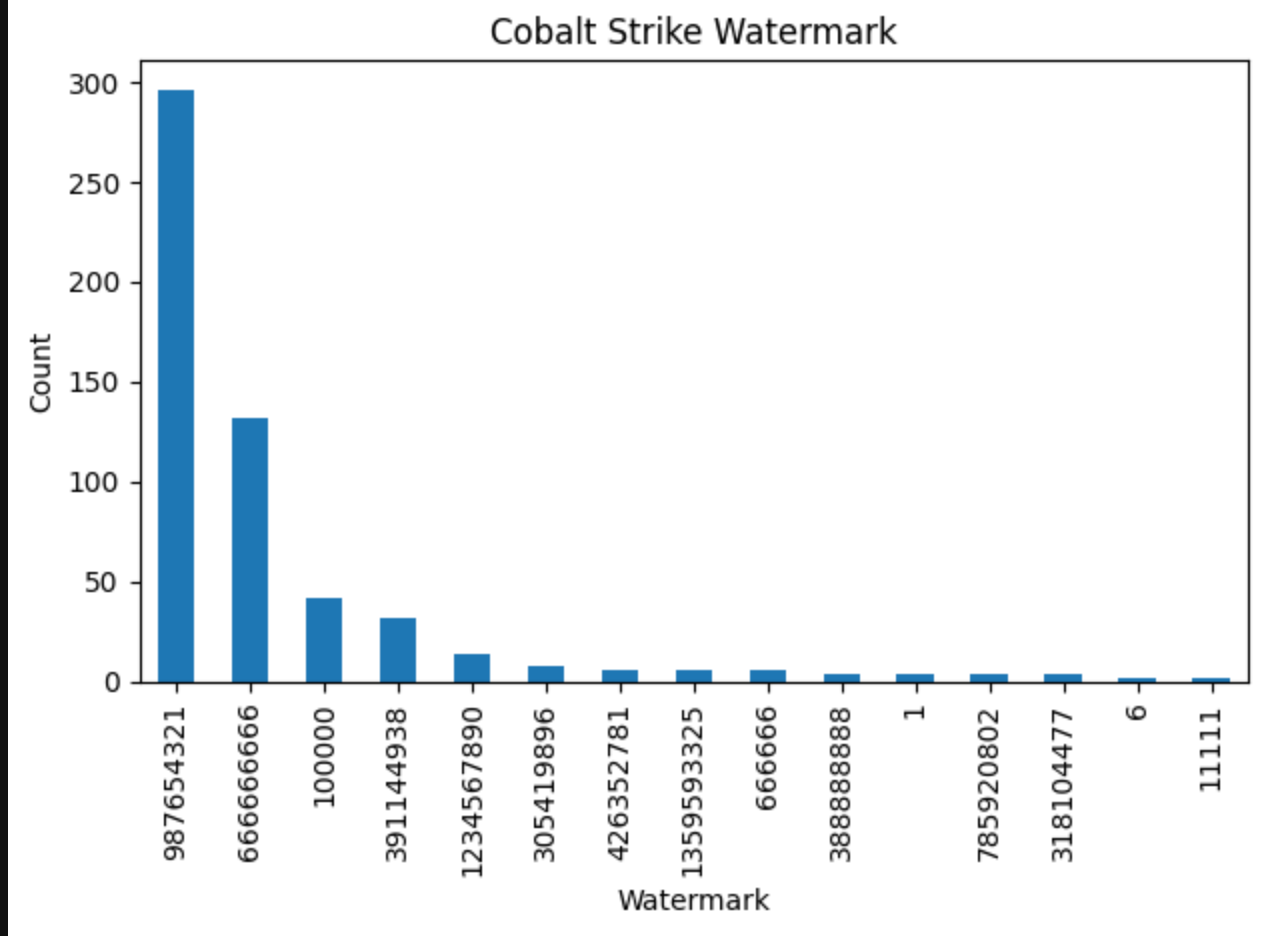

Group By Watermark

When listing all unique watermarks, there were only 15.

Taking the user-agent string from watermark 6, a Censys query can be built to find what else might be using the same user-agent.

Mozilla/5.0 (compatible; MSIE 9.0; Windows NT 6.1; WOW64; Trident/5.0; MALC)

- 8.137.149[.]67

- 120.79.229[.]151

- 115.120.245[.]134

Hunt.io wrote about another unique watermark (688983459) being used by just 7 IPs. Although the dataset I'm looking at includes version 4.10, I did not observe that specific watermark.

version settings.SETTING_WATERMARK

Cobalt Strike 4.9 (Sep 19, 2023) 987654321 145

666666666 131

Cobalt Strike 4.8 (Feb 28, 2023) 987654321 130

Cobalt Strike 4.7 (Aug 17, 2022) 391144938 32

Unknown 100000 21

Cobalt Strike 4.5 (Dec 14, 2021) 100000 21

Cobalt Strike 4.7 (Aug 17, 2022) 987654321 14

Unknown 987654321 7

Cobalt Strike 4.3 (Mar 03, 2021) 426352781 6

Unknown 1234567890 5

Cobalt Strike 4.4 (Aug 04, 2021) 1234567890 5

Unknown 305419896 4

Cobalt Strike 4.0 (Dec 05, 2019) 305419896 4

Cobalt Strike 4.3 (Mar 03, 2021) 1234567890 4

Cobalt Strike 4.5 (Dec 14, 2021) 666666 3

Cobalt Strike 4.2 (Nov 06, 2020) 1359593325 3

Unknown 666666 3

1359593325 3

1 2

Cobalt Strike 4.4 (Aug 04, 2021) 785920802 2

Cobalt Strike 4.5 (Dec 14, 2021) 11111 2

Cobalt Strike 4.1 (Jun 25, 2020) 388888888 2

Unknown 318104477 2

388888888 2

785920802 2

Cobalt Strike 4.2 (Nov 06, 2020) 1 2

Cobalt Strike 4.10.1 (Dec 10, 2024) 318104477 2

Cobalt Strike 4.4 (Aug 04, 2021) 6 1

Unknown 6 1

666666666 1Another way of using this data is to take the existing watermarks and develop another Censys query for proactive monitoring. Right now this query returns 189 results which is a great start.

Comparing Architecture

With both x86 and x64 config files available along with single IPs using multiple ports, I thought it'd be interesting to see what's different between them. A second dataframe was created that split columns based on architecture so that differences could be easily denoted by _x64 or _x86 at the end of each column name.

Taking an IP that uses multiple ports, it's much easier to pull every URI path and SPAWNTO process.

| ip | port | uri_path_x86 | uri_path_x64 | settings.SETTING_SPAWNTO_X86_x86 | settings.SETTING_SPAWNTO_X64_x64 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 281 | 83.229.125.47 | 8022 | /static/jquery.min.js | /static/jquery.min.js | %windir%\syswow64\werfault.exe | %windir%\sysnative\werfault.exe |

| 282 | 83.229.125.47 | 8080 | /static/jquery.min.js | /cdn/jquery-3.6.0.js | %windir%\syswow64\werfault.exe | %windir%\sysnative\werfault.exe |

| 283 | 83.229.125.47 | 8090 | /cdn/jquery-3.6.0.js | /static/jquery.min.js | %windir%\syswow64\werfault.exe | %windir%\sysnative\werfault.exe |

This can also be useful to find differences in a certain column. Taking user-agent strings as an example, some strings are more common in x64 beacons than they are in x86.

| arch | x64_ips | x86_ips | ip_diff |

|---|---|---|---|

| settings.SETTING_USERAGENT | |||

| Mozilla/5.0 (iPhone; CPU iPhone OS 12_1_3 like Mac OS X) AppleWebKit/605.1.15 (KHTML, like Gecko) Mobile/16C104 | 8 | 8 | 0 |

| Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 7.0; Windows NT 5.1; Trident/4.0) | 7 | 4 | 3 |

| Mozilla/5.0 (compatible; MSIE 9.0; Windows NT 6.1; WOW64; Trident/5.0; yie9) | 7 | 3 | 4 |

| Mozilla/5.0 (compatible; MSIE 9.0; Windows NT 6.1; WOW64; Trident/5.0; NP06) | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 8.0; Windows NT 6.1; WOW64; Trident/4.0; SLCC2; .NET CLR 2.0.50727) | 6 | 5 | 1 |

These top five user-agents that are more common in x86 beacons.

| arch | x64_ips | x86_ips | ip_diff |

|---|---|---|---|

| settings.SETTING_USERAGENT | |||

| Mozilla/5.0 (iPhone; CPU iPhone OS 12_1_3 like Mac OS X) AppleWebKit/605.1.15 (KHTML, like Gecko) Mobile/16C104 | 8 | 8 | 0 |

| Mozilla/5.0 (compatible; MSIE 9.0; Windows NT 6.0; Trident/5.0) | 4 | 7 | -3 |

| Mozilla/5.0 (compatible; MSIE 9.0; Windows NT 6.1; WOW64; Trident/5.0; MANM) | 3 | 6 | -3 |

| Mozilla/4.0 (compatible; MSIE 7.0; Windows NT 5.1) | 3 | 6 | -3 |

| Mozilla/5.0 (compatible; MSIE 9.0; Windows NT 6.1; Win64; x64; Trident/5.0) | 3 | 5 | -2 |

Conclusion

Malleable C2 profiles introduce a wide range of possibilities for disguising C2 traffic, making beacon tracking significantly more challenging. Critical indicators often reside within the configuration file itself and if the host has gone stale, that configuration won't be recoverable. This living dataset of configuration files eases the analysis of beacon behavior without relying solely on post-incident artifacts. Since this data is collected independently of individual incidents, it remains largely unbiased and provides a clearer view of real-time Cobalt Strike activity.